Dreamwork is one of the central techniques of dream analysis psychotherapy, allowing symbolic formations of the deep unconscious to communicate their insights and to guide the patient toward greater wholeness. Dreams make emotionally charged material accessible to consciousness, quickly and safely. They help give focus to the therapeutic process and indicate the direction of treatment. Dreams provide important clues about the origins of the client’s pain and what issues or emotions need to be examined and resolved. Working with dreams can be a potent catalyst of intrapsychic and behavioral change, and has a unique capacity to promote healing from within.

Dreamwork is one of the central techniques of dream analysis psychotherapy, allowing symbolic formations of the deep unconscious to communicate their insights and to guide the patient toward greater wholeness. Dreams make emotionally charged material accessible to consciousness, quickly and safely. They help give focus to the therapeutic process and indicate the direction of treatment. Dreams provide important clues about the origins of the client’s pain and what issues or emotions need to be examined and resolved. Working with dreams can be a potent catalyst of intrapsychic and behavioral change, and has a unique capacity to promote healing from within.

Dream Analysis Psychotherapy

Dreams are like icebergs rising out of the deep waters of the unconscious. Some are icebergs of the past, helping us understand past traumas and undigested memories, and thus are retrospective. Dreams are integrative in that they enable us to perceive and reconcile our many conflicting sub-personalities. They are also prospective or anticipatory, icebergs of the future, depicting what is emerging, images of what the individual potentially can become. Looking backward and forward simultaneously, the dream’s essential function is always to expand the aperture of consciousness, the circumference of perception, the sphere of identity.

The main dreamwork technique I utilize is a willingness to inquire with open curiosity into the current significance of every character, place, and action in the dream—each of which refers to the dreamer’s intrapsychic condition and current life situation. The often humorous and paradoxical messages revealed by dreams jog loose new perceptions. Received reverently, each dream becomes a pearl from the depths of the ocean of consciousness. Reflection on the dream’s mystery evokes a feeling approaching religious awe; we become filled with amazement at the psyche’s capacity to portray its own condition.

In this brief excerpt I will recount some examples of how dreams can influence the therapeutic process, evoking central themes that become the focus of treatment. For example, Bob, a man in his mid forties beginning a course of psychotherapy, had this dream: “I am six years old. I am with my mother and we are cleaning out the closets.” The therapist is immediately drawn to the emotional significance of events in the client’s sixth year and the need to sort through whatever has been hidden in the closet. Many family secrets were brought out of hiding in subsequent therapy sessions. I learned about the domestic violence and alcoholism that had been closely-kept family secrets. Bob is currently in a deep depression after the breakup of a relationship. As he begins to examine his anger, his previously unrecognized tendency to act abusively toward women, his sadness, and his need to accept his solitude, he dreams: “I am on my hands and knees in front of my bed potting a cactus plant.” The cactus plant represents Bob’s prickly personality. When asked what the further significance of a cactus might be, he said, “A cactus can live in a desert for a long time with very little water, and it finds its juice within its own body.” The cactus is a symbol of his need to find juice or aliveness in the desert of his solitude, rather than looking to women and relationships for excitement. Bob has to learn to live with himself, to care for himself. Being on his hands and knees suggests the emergence of humility.

A simple dream often carries deep emotional meaning. In her second therapy session a woman reports, “I dreamed that I am in the store where I work, counting a stack of money. A bunch of money is missing.” The client offers the interpretation that, “Being robbed in the dream reminds me of how I was robbed of my childhood. I never got a chance to be a kid, to be cared for and pampered. I was short-changed.” As we explored this theme, Jill recounted to me ways she had been parentified, being forced to function as a little adult in her family from the age of six. She began to understand more clearly how much grief and anger she still carried from her lost childhood. But the dream has another meaning: money is missing. Jill is grappling with serious money issues. She is not earning much and her self-esteem is very low. When I ask for her associations to “money is missing,” she says, “I feel like I’m not worth anything.” Each dream image is a hologram of the inner world full of condensed meanings.

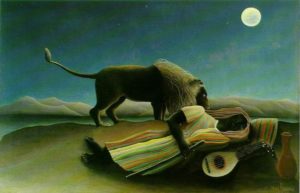

A woman named Wendy, with an extensive history of childhood abuse, had a lot trouble expressing anger and standing up for herself, and she was frequently victimized by others. She dreamed: “Some friends take me to an animal rescue place with wildcats, bobcats. They show us around, show us how they talk to the animals and handle them. A big lioness or wildcat jumps me and puts her claws into my leg. I talk to her and try to stay calm.” Asked for her associations to the wildcat, Wendy said, “It is powerful, untamed. Anger and aggression are hard for me. The lioness is a creature that knows how to show its claws.” The dream suggested a need for Wendy to rescue and shelter the fierce, animal part of herself. Where previously she had been like an innocent lamb or a victim, with little ability to stand up for herself, this dream heralded the emergence of a positive capacity for aggression, will, self-defense, self-protection. A week later Wendy reported standing up to someone who had wronged her, writing a letter to detail her grievance and to express her hurt and anger. The dream coincided with the emergence of her inner wildcat.

Tanya, a woman in an asexual marriage, dreamed that there was a massive wall between the living room and the bedroom of her home. The wall symbolized her resistance to sexuality, her need to maintain boundaries to defend against physical and emotional injury. Contemplating this image proved helpful not only to the dreamer but also to James, her husband, who was able to understand for the first time the depth of Tanya’s fear of sexual intimacy. Tanya was able to recognize how her body had become frozen in fear, creating an impenetrable barrier to any sense of closeness. Working with this dream proved valuable in enabling Tanya and James to begin dismantling the wall between them.

An ex-priest dreamed that he entered a cave where he found an altar, in front of which lay a sleeping wolf. The wolf symbolized both his feelings of being a lone wolf, fending for his own survival now that he had left the Church, but also his long dormant (sleeping) animal nature, his sexual desire, his hunger for embodied, passionate life.

Dreams provide important insights about the therapeutic relationship. A fifty-four-year-old woman named Ann presented numerous dreams that referred to transference feelings toward her therapist. In one, Ann sat in the back of a lecture hall as her therapist gave a lecture. She could not decide whether to stay or leave. Profound ambivalence about the therapeutic process is demonstrated. Should she stay or flee? The therapist also receives information from the dream that Ann may perceive him as overly intellectual or “preachy.” In another dream, her therapist disappears unexpectedly, reflecting her fear of abandonment by him.

Dreams deepened Ann’s treatment immeasurably. Later, she dreams, “I am a flightless bird.” Her flight and freedom of spirit are inhibited. She is dysphoric, chronically depressed, unable to find any pleasure in daily living. When I asked her to explore this further, she described how caged-in she felt in her marriage, how her husband actively thwarted her movements toward greater autonomy, and how little fun they had together.

Then Ann dreams, “A man is at my window, angry and menacing. There is something wrong with him. I feel concern for him, for he is in desperate need of help.” Ann has a history of incest, so issues of boundary intrusion (angry man at the window) are central. She herself is desperate for help. But conflicted feelings toward her childhood abuser are also reflected, including fantasies of helping or rescuing him. Ann has suffered from a phobic aversion to sex and has been unable to make love with her husband for over twenty years. This dream helped Ann understand how her refusal of sexuality had started out in her childhood as a self-protective measure, to keep out the intruder. She also associated the man in the dream to her husband, who had become increasingly angry with her. She was able to see that, while she was repulsed by her husband, she was also terrified by the prospect of leaving him because, she believed, he needed her to take care of him.

Dreams can illuminate complex relationship issues that may be reenacted in the therapeutic transference. Ann dreamed: “A little girl is playing innocently on a lawn, running around and catching fireflies in her hands, laughing and shrieking with joy. Then a small buffalo comes over and starts bumping his head against her. She’s not in danger, but she feels anxious and wishes he would go away. She wishes there were someone around who could make the buffalo go away, but there isn’t anyone to help her.” Ann’s dream of torment by a hairy animal evoked childhood memories of sexual violation by her stepfather, her inability to protect herself, feeling abandoned by her mother, her longing for protection. The theme of innocence, its loss and recovery, became central threads of our discussion. The buffalo also reminded Ann of her husband’s insistent sexual demands and his angry frustration with her unresponsiveness. This material became the focus of the next several sessions. But when asked for further associations to the buffalo, Ann was reminded of her therapist. She said, “The hairy buffalo reminds me of your beard and long hair.” I said, “You and I have been butting heads the last few weeks about some things.” She laughed and said, “Actually, it was a very skinny, scrawny buffalo!” We both laughed. This dream opened up new space in our intersubjective field. She could talk about feeling anxious about whether she could find comfort and protection in therapy. We could also talk about our evolving therapeutic relationship and what it felt like that at times I challenged and confronted her.

Several months later, Ann dreams that she is wearing the red dress she wore the night before her wedding, a dream that evokes the expectancy and excitement of marriage, and feelings of being young, beautiful, sexy, and desirable. Later she dreams that she is pregnant for the third time. She is pregnant with herself; the dream portends inner rebirth and renewal. This dream coincided with her beginning sex therapy with her husband.

Dreams reveal and intensify our emotional states. A man dreamed he went to a Thanksgiving party but there was no substantial food there, only a few pieces of fruit and some small snacks. Some children arrived at the party and were disappointed that they were not going to eat. This dream encapsulated an emotional experience of deprivation and lack of nurturance that he realized he had felt since childhood.

I have found dreamwork to be an essential tool in my therapeutic work, portraying my clients’ central concerns, deepening access to their most emotionally charged material, and leading directly to increased self-awareness and personal integration. Dreams are like a fountain flowing from our inner depths that can be of inestimable value to the process of psychotherapy.

Copyright Greg Bogart 2000. All rights reserved.

This material became part of the origins of Greg’s book Dreamwork and Self-Healing (Routledge, 2009).

A modified version of this paper appears in Dreamscaping: New and Creative Ways to Work with Your Dreams,

(Edited by S. Krippner & M. Waldman) (Los Angeles: Lowell House, 2000).